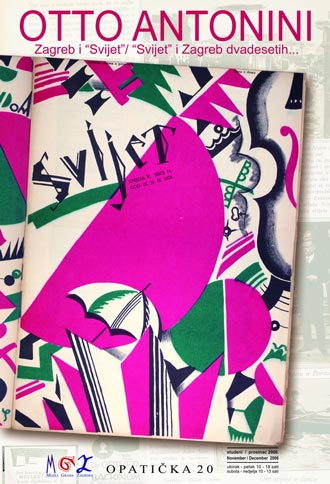

Otto Antonini: Zagreb and "Svijet" - "Svijet" and Zagreb in 20s

Exhibition concept: Željka Kolveshi

Exhibition design: Željko Kovačić

Poster design: Miljenko Gregl

On February 6, 1926, Zagreb welcomed the publication of its first modern magazine, the illustrated weekly Svijet [World] (1926-1936), magazine for social life. When the idea of its initiator, first editor and long-time illustrator Otto Antonini was thus brought to fulfilment, two stars shone out in the Croatian news firmament. The first was a new weekly with a middle-class orientation, conceived to feature up-to-date content, with stories from social goings-on in the field of entertainment, fashion, music, art, sport, film and theatre, politics and business, as well as travelogues, serial novels, scores of light music, humour and features of interests, local and world, the novelties and sensations that, we can say today, marked the period of the twenties. In line with the debut of a new era of European-wide events and fashions, the decorative Art Deco style became omnipresent and irresistible, covering the essential dimensions of the time known variously as the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties, the Swinging Twenties, for novelties that flooded the world, including Zagreb: jazz bands with new sounds and new dances, the Charleston and the craze for dance music to the gramophone or the newly-opened Palais de danse clubs, the production of the first talkies, ever-higher hemlines and shorter hairstyles, the popular bubikopf or bob. There were also competitions for bathing beauties in the summer, night clubs, cabarets, reviews and stars as well as the state of the art in technology, the plane and the airship, the vast steamships and transoceanic crossings.

On February 6, 1926, Zagreb welcomed the publication of its first modern magazine, the illustrated weekly Svijet [World] (1926-1936), magazine for social life. When the idea of its initiator, first editor and long-time illustrator Otto Antonini was thus brought to fulfilment, two stars shone out in the Croatian news firmament. The first was a new weekly with a middle-class orientation, conceived to feature up-to-date content, with stories from social goings-on in the field of entertainment, fashion, music, art, sport, film and theatre, politics and business, as well as travelogues, serial novels, scores of light music, humour and features of interests, local and world, the novelties and sensations that, we can say today, marked the period of the twenties. In line with the debut of a new era of European-wide events and fashions, the decorative Art Deco style became omnipresent and irresistible, covering the essential dimensions of the time known variously as the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties, the Swinging Twenties, for novelties that flooded the world, including Zagreb: jazz bands with new sounds and new dances, the Charleston and the craze for dance music to the gramophone or the newly-opened Palais de danse clubs, the production of the first talkies, ever-higher hemlines and shorter hairstyles, the popular bubikopf or bob. There were also competitions for bathing beauties in the summer, night clubs, cabarets, reviews and stars as well as the state of the art in technology, the plane and the airship, the vast steamships and transoceanic crossings.

The second brilliant star was Otto Antonini (1892-1959) who brought the new decorative style of art into the graphic design of the journal, the Art Deco style, according to which Svijet was to be a unique phenomenon and a synonym for the promotion of this style in Croatian cultural history, from the perspective of its media influence of the formation of the popular culture of the 1920s. From his long period of work in Svijet, from the very beginnings to the end of 1932, he created hundreds of illustrations for headline news on covers and back pages, for special issues, for novels and journalists' stories, all of which defined the visual identity of Svijet. The high graphic standard of the magazine could stand world comparisons, and was the basis of the idea of this publishing venture with which the Tipografija firm set out to capture new audiences and markets.

The launch of the magazine was accompanied by well-designed advertising. At the beginning of 1926 a poster and a subscription form were printed, announcing the issue of the new weekly at the beginning of February. Antonini provided the artwork for the Svijet trademark and for other advertising materials. The symbolism of the artwork aimed at marketing the basic idea of this weekly combined wording and image in a graphic design based on stylisation, the black and white contrast of ground and typography with the accent on the pink of the image of the globe – world (Svijet) in the centre and white newspaper sheets that fluttered in this universe of news. The word Svijet itself, blazoned in white and the wording of the announcement, was based on a typeface that was used to create a recognisable sign. The trademark of Svijet would regularly appear on the frontispiece of the bound copy of each half-year down to the end of 1936, up to which time it came out in the same form.

The subscription forms advertised the advantages of subscribing at a reduced price for subscribers of other Tipografija productions – Jutarnji list, Obzor and Večer. Svijet, then, could be delivered to the home address, bought in any kiosk, bookseller or from street vendors, as quickly authorised in the new Press Law.

Svijet was launched with the idea of it being a mass medium the content of which was meant for all ages of a broad circle of readers. The new year started with Svijet, as if the first number of the review in 1930 wanted to say, with its cover suggestively illustrated and featuring the slogan EVERYONE READS IT / EVERYONE LOVES IT, that Svijet was a must for old and young, child to grandfather, teenager to fashionable lady, boy and son, a couple of peasants... And in order to make sure of lasting circulation, an attempt was made to keep readers' interests up with various marketing campaigns. Almost every winter season Svijet announced competitions for the selection of the most elegant outfits or carnival costume, and in the summer ran a bathing beauty competition. It kept up the interest of the child reading public with a call to compose collage pictures, the parts of which had to be collected from successive numbers, the main prize to the little winner being a portrait drawn by Otto Antonini.

The novelties in world photographs and the art of the Antonini illustrations made Svijet the most glamorous and popular magazine in the country. This is particularly highlighted in the preliminary announcement of its publication: “Svijet will put the emphasis on pictures and illustrations”. In addition, it says that it will primarily give current shots of all the most important events, domestic and world-wide: “Secondly, Svijet will pay particular attention to our domestic social life, and will, along with the copy, have original drawings and illustrations from an artistic hand. The whole of the artistic and production side of the paper has been confided to our well-known painter Otto Antonini”.

Antonini's illustrations, then, were meant to keep up with current affairs “from the artistic, theatrical and elegant world and life... the life and work of woman in the country... sport, fashion, film, dance, entertainment, cultural events, humour with caricatures – there will be all this in abundance”.

The first part of the mission, the publication of current news and photos from the world was carried out by Svijet buying in news and photographic material from the world news agencies, which regularly arrived at the address of the editorial office in Preradović Square no. 9. Materials came from the Atlantic agency, Berlin; Meurrise et Rol, Paris; Globophot, Berlin; Central Press, London; Foto Bonney, Paris. Foto Bonney, which was named after the American photographer Therese Bonney, supplied some twenty countries with its services. It also supplied a lot of fashion photography, according to which Antonini did some of his fashion illustrations, as well as other content in which this remarkable woman recorded the visual chronicle of Paris in the Art Deco period.

The second part, the presentation of domestic social life in original illustrations was equally successfully carried out by Antonini. His best illustrations fell nothing short of the artwork of the best magazines of the type in the world, like the Parisian L'Esprit Nouveau, L'Illustration, Arts decoratifs, the contemporaneous American Variety and the New Yorker, the fashion magazines Harper's Bazaar in New York, the Berlin Die Dame, the Parisian, English and American editions of Vogue, Fortune, journals that came out in Spain and South America. He achieved a high level in quality and style by intuitively pulling together his drawing skills, his graphic experience and the creativity and innate elitism of his approach to art and social life.

Although he was editor only of the first 18 issues of Svijet, it is clear that Antonini defined the editorial graphic style, the artistic and production side, which did not change until the end. And that he was able to carry it out at a remarkable level of quality from the beginning was related to his being able to depend on the conditions provided, of both production and those of his closest associates.

Tipografija, the printer's, had bought the most up to date equipment in the country in 1926, and the photographs in Svijet (16 pages in large quarto format) were printed in etchings, and the cover and other illustrations in offset. The quality of the print as against the original was 1:1. The manager of the lithographic department of the press, with whom he worked most closely, was Vladimir Rožankowski (1872-1939), experienced graphic expert, a lithographer who as early as 1898 had founded his Chromolithographic Institute and Printer's in Zagreb. A better close and direct associate, Antonini could not have found. They had already worked closely and successfully together in the artistic and satirical magazine called Šišmis [Bat], which Antonini had launched, and Rožankowski printed and published. It came out fortnightly over three years (1915-1917), and it was here that Antonini obtained his first experience in graphic design, designing, as in Svijet, the covers, the adverts and illustrations to the text, but in the style of Secession, with marked Expressionism, heightened by the events of the wartime period. In his excellent drawing he created numerous caricatures, using a visual expression appropriate to a magazine of the kind, which he was later to modify in the making of sketch portraits of celebrated and anonymous persons and events, and also used it where necessary in the many illustrations in Svijet.

A second equally important co-worker, and one who complemented his talents, was Zvonimir Vukelić (1876-1947), author, journalist and columnist in Jutarnji list, with the reputation of the editor of the first-ever illustrated paper in the country Ilustrovani list (1914-1915). As editor in Svijet, working under the penname of Zyr Xapula he wrote satirical texts “little momentary pictures of our society, our people, their weaknesses...” which spoke quite realistically about the society of their contemporaries, just as did the drawings and caricatures of Antonini, which illustrated the text. The openness and breadth of Svijet in the commentary on social events is evinced by the issue of February 9 1929, in which there was a big story about the journalists' dance in the Esplanade Hotel, shown in the copy and the photographs as the most elite event of the season (Antonini and his wife were among the guests), and then just a few pages later came the Zyr Xapula text On the eve of the Elite Dance of the Zagreb journalists, in which he made witty fun of all the circumstances of the ridiculous preparations and financial consequences that attended the participants in the dance. The author of the illustrations, caricatures in fact, Antonini readily and probably with a degree of self-irony, commented on an event in which he had himself taken part.

Otto Antonini succeeded in identifying his own artistic vein, taking on board the Art Deco style, which was practically innate in this gentleman painter, the style of the times in the artistic period of the twenties, which was marked by stylistic pluralism, in the general mood of the intellectual climate of the time. His artistic interests and the visual oeuvre that he created on the pages of Svijet were a synonym for the lifestyle of the age, or rather, the Zagreb lifestyle of the period.

His manners included sophistication and refinement, a passion for travel, and although contemporaries described him as a retiring artist, he nevertheless had a very wide range of social interests. He was attracted by the new creations of Parish fashions, modernism in town planning, architecture and design, the challenges of aircraft, and the speed of automobiles. He was a member of the Croatian Auto Club, kept up with promotional drives, and spent a fashionable life at suppers in their social rooms at 19 Zrinjevac. He was ready to go in for the new sports; he was founder and member of Zagreb Golf Club and played on the course at Maksimir; he was a member of the Marathon Club and did kayaking on the Sava River. He spoke Italian and German, and was welcome in all society. He was a member of the jury that chose Štefica Vidačić as the first Miss Yugoslavia in 1926, and of the Concours d'elegance at the spring Zagreb Fair in 1931, 1932 and 1938. He was to be found at social events, charity occasions, carnival balls, at parties of artists and at dinner-dances in the Esplanade Hotel, the Music Institute, the Cafe-Club, or the Auto Club, but always with pad and pencil, sketching situations, peoples, get-ups...

All this experience was funnelled into the illustrations in Svijet, showing by his own example that art was a reflection of the lifestyle of the period, not just the artistic forms of style.

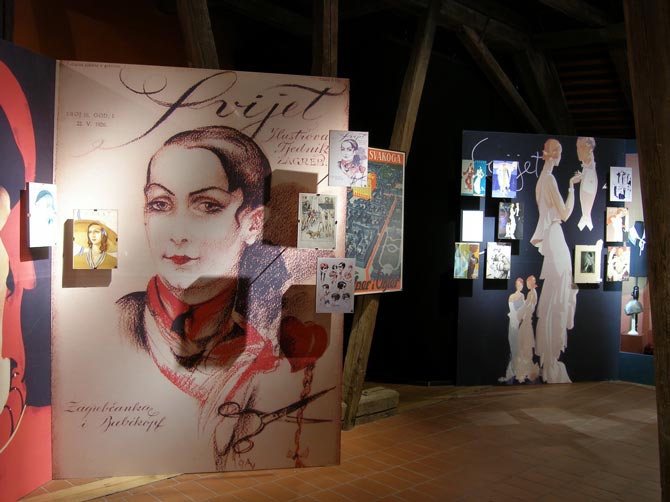

The basic constant of this exhibition developed from the synergy between the personality of Otto Antonini, his art and the urbanity of Zagreb of this period. Hence at the exhibition, as well as in the catalogue, there is a constant interweaving of the contents in the visual art and the features of the biography of Antonini himself. In this way I endeavoured to obtain a confirmation that the biography of the author was in key with his art, and that in turn with the period in which it was created.

Željka Kolveshi

Pictures from the exhibition

photo Miljenko Gregl, ZCM

Exhibition catalogue

Exhibition catalogue

Kolveshi, Željka. Otto Antonini : Zagreb and "Svijet" / "Svijet" and Zagreb in 20s.

Zagreb : Zagreb City Museum, 2006

Related published papers

Kolveshi, Željka. Otto Antonini : “World” and Zagreb of Twenties... // The Regent Esplanade Zagreb Luxury & Lifestyle Magazine. II, 2(2007), pp. 68-74.