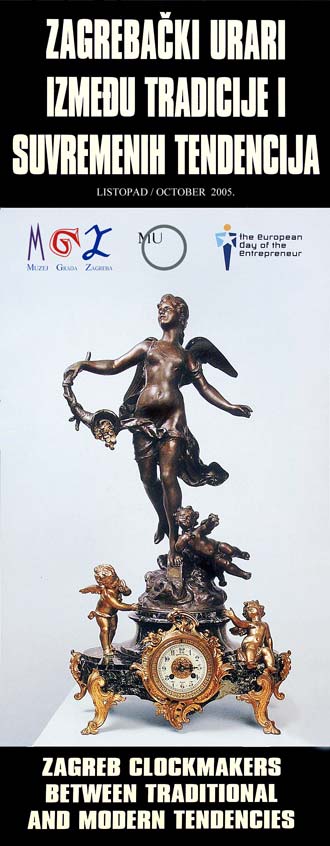

Zagreb Clockmakers between Tradition and Modern Tendencies

Zagreb City Museum in collaboration with the Museum for Arts and Crafts, Zagreb

Exhibition concept: Vesna Lovrić Plantić

Exhibition design: Miljenko Gregl

Poster design: Miljenko Gregl

The oldest known data on clockmakers in Zagreb originate from the 16th century. The documents describe that the repairs of public clocks in Zagreb, i.e. the Cathedral clock as well as the clock on St. Marc's Church were done by locksmiths who were, thus, through certain period of time, specialized for clockmaker's trade.

The oldest known data on clockmakers in Zagreb originate from the 16th century. The documents describe that the repairs of public clocks in Zagreb, i.e. the Cathedral clock as well as the clock on St. Marc's Church were done by locksmiths who were, thus, through certain period of time, specialized for clockmaker's trade.

On the other hand, makers repairing domestic clocks were not mentioned until the second half of the 18th century. From their names and the archive data we can see that they were mostly foreigners who settled in Zagreb and obtained the citizenship. The clockmaker Benedict Schwabbauer from Bavaria, for example, became the citizen of Zagreb in 1777 and was famous for his special skills in making smaller clocks.

The oldest known clock made in Zagreb was a bracket clock from 1776 by clockmaker Thomas Leuthner. The larger number of clocks originating from the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century was made by clockmakers from Zagreb: Anton Geisler, Mathias Onitsch, Heinrich Rosenberg, Franz Xaver Rummel, Peter Mezlyak, Carl Eisenbarth, Wilhelm König and others.

Since that time the number of clockmakers working in Zagreb has gradually increased. The data from the end of the 19th century mention almost fifty clockmakers with registered clockmaker's trade. It was common in those times that the clockmakers, searching for work, move from one town to another. Joseph Heichele, for example, worked both in Zagreb and in Rijeka, which can be documented by his signature on the preserved clocks. Lorenz Wilhelm Pehr came to Zagreb from Ljubljana and in 1843 he advertised his clockmaker's skills in order to get new orders and repairs. During the next ten years he was mentioned as the clockmaker who worked in Karlovac.

In 1835 the clockmaker Carl Eisenbarth advertised his shop near the Stone Gate in Zagreb emphasizing that he made clocks in the best clockmaking tradition which were then sold in his shop. In those times clockmakers made clock movements themselves, which would change several decades later.

In mid 19th century more and more clocks were imported and clockmakers only put their signatures on them as a sign of quality. From that time they mostly dealt with trade and repairs. Sometimes musical mechanisms with patriotic songs were built in the already finished clocks. Peter Semmelroth, thus, advertised that he could build in the music mechanism made of steel which played the folk songs such as “Još Hrvatska ni propala” and “Nek se hrusti šaka mala”. The same clockmaker announced that his supply of clocks came from “the first and the best sources” and each clock with his name was given a two year warranty.

On trade fairs, that started to be held in mid 19th century both in our country and abroad (the first Croatian trade fair was held in 1864 in Zagreb) clockmakers from Zagreb also exhibited.

The Chamber of Trade and Commerce in Zagreb, in its report of 1885 mentioned that the number of clockmakers in this area from 1881 to 1885 increased from 32 to 47. After the revocation of the guild regulations in 1860 and 1872 and the liberalization of the clock import the Croatian clockmakers were not able to compete with the cheaper clocks from abroad, so pocket watches were solely purchased in Switzerland (less in the United States) and domestic clocks were mostly obtained in Vienna and Germany. The Chamber financed a professional education of clockmakers in Germany, France and Switzerland. Most of them, including also those from Zagreb, turned into the clock sellers, retaining only a part of their clockmaker's trade: repairs and spare parts supply. They cooperated with carpenters, building in the movements in clock cases which, by their designs, complied with the rest of the furniture in the apartments. However, they did not make those movements, but purchased them in specialized factories and adapted the movements to individual clocks.

For the Millennium Exhibition in Budapest in 1896 Mavro Knez supplied one movement for the clock case for “pisnička soba od orahovine” (the study made of walnut) exhibited by the Kovačić brothers, and the other one for Josip Šeremet for his clock in “soba za učenje i stanovanje djece” (the children's room). The movements for the clock in the dining room made out of oak in the early Renaissance style by the carpenter Ivan Budicki from Zagreb as well as for the clock in “gospojinskom boudoiru u kasnoj renaissance” (the lady's late Renaissance boudoir) made by Ivan Postružin, were supplied by Dragutin Vasić, a clockmaker and a clocktrader from Zagreb.

At the beginning of the 20th century the number of clockmakers and traders in Zagreb was increased, which can be documented by numerous trade licences issued at that time. The clockmakers, beside their usual tasks such as repairs and spare parts, had also shops where they sold clocks and watches, often combined with other crafts: in 1892 Mavro Drucker registered both clockmaker's and mechanical workshop in Zagreb in Ilica 38. Bruno Wolf registered clockmaking and trading in silver and gold in Zagreb, in Duga ulica 8.

Between the World Wars Zagreb was the center of clockmaker's trade in the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Beside the clockmakers who dealt with assembling and trading of clocks and watches (Vasić, the Pick brothers, Berman, Perok, Passticy and others) there were also the clockmakers who continued to observe the tradition of the profession and who educated the generations of excellent clockmakers. One of them was Drago Novak who owned the shop in Ilica 24 and whose apprentice was Josip Ivanković, the doyen of the clockmaker's trade in Zagreb and the author of the first Croatian clockmaking handbook printed in Zagreb in 1947. Mato Barać maintained the public clocks in Zagreb in the forties and the fifties, and from then until today this work has been done by three generations of the Lebarović family who have been making large clock movements or their parts themselves.

Several first-class watchmakers work in Zagreb today who are familiar with all technological innovations which enables them to repair and maintain the top-quality watches such as Rolex, Cartier, Omega and others, continuing at the same time the centuries-long tradition of clockmaker's trade in Zagreb.

Vesna Lovrić Plantić

Pictures from the exhibition

photo Miljenko Gregl, ZCM