Phallus Against Spells - The Archaeological Collection of Dr Damir Kovač

Exhibition concept: Dr Damir Kovač, Morena Želle

Exhibition design: Željko Kovačić

Poster design: Miljenko Gregl

Superstition has accompanied man from the very beginning to the present. In response to the phenomena of life, problems, birth, and death, man has found objects, words, and gestures to eliminate his vague fears. The ancient world was full of symbolism, religious and magical; as well as belief in the various properties of objects and their effectiveness, inherited from earlier periods and cultures, particularly Egypt and Greece. The phallus represents a symbol of procreative power, the creation of seed as the active principle. Esoteric or erotic qualities are not necessarily attributed to the phallus; it simply expresses the procreative power that is worshipped in this form in many religions. In modern psychoanalytical texts, the use of the terms phallus and phallos has become increasingly distinguished; phallus is used for the male physical organ, while the term phallos emphasizes the symbolic value. Phallic meaning can be attributed to: a foot, a thumb, a column, a tree trunk...

Superstition has accompanied man from the very beginning to the present. In response to the phenomena of life, problems, birth, and death, man has found objects, words, and gestures to eliminate his vague fears. The ancient world was full of symbolism, religious and magical; as well as belief in the various properties of objects and their effectiveness, inherited from earlier periods and cultures, particularly Egypt and Greece. The phallus represents a symbol of procreative power, the creation of seed as the active principle. Esoteric or erotic qualities are not necessarily attributed to the phallus; it simply expresses the procreative power that is worshipped in this form in many religions. In modern psychoanalytical texts, the use of the terms phallus and phallos has become increasingly distinguished; phallus is used for the male physical organ, while the term phallos emphasizes the symbolic value. Phallic meaning can be attributed to: a foot, a thumb, a column, a tree trunk...

In antiquity, the phallus represented a common charm-amulet in the most varied forms, materials, and sizes, chosen as a protection from spells.

What is an amulet? An amulet can refer to a specific deity, placing the one who wears the amulet under the protection of that god, or to an animal, in which case some of the traits of that animal become available to the one bearing that amulet. Archaeologists discovered long ago that prehistoric man wore amulets. It seems understandable that non-scientific reflection would lead to the concept that it is positive to wear a symbol of power or importance as protection.

Throughout the later ages, the phallus was ignored because of its immodest or inappropriate nature, although clay, plaster, bronze, or marble vases, lamps, statues, and frescoes and mosaics of the ancient Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans are full of depictions of erotic, hermaphroditic, and priapic images.

By not taking account of these depictions, we are being falsely moralistic, denying ourselves valuable data for the history of various periods and the study of artistic workshops, and we are neglecting an important aspect of classical civilization. To ignore such creations would mean neglecting and degrading our knowledge of art of perhaps the most refined accomplishment that the freedom of inspiration and artistic expression has ever created.

It would be inaccurate to say that the Romans were obsessed with sex because of the frequent finds of phallic pendants and grotesque figures in excavations, and the frequently cited proverb bonus penis pax in domo. Let us leave aside Tiberius and Nero, who are perhaps better known for their debauchery than their political roles. Many have remembered Messalina, the wife of the emperor Claudius, who gave herself to passing strangers in the quarter of ill-repute Suburbia. Leaving aside the sensual lasciviousness of the aesthete and skeptic whose main care was to lead an inimitable and easy life full of pleasure, we should instead remember the anxieties of a person faced with the unknowns of life and death, the unease induced by human destiny. This is when superstition appears, which exists from the baneful influence held by certain words or images, and particularly certain individuals in terms of parts of their attire, or a certain eye color, or merely their presence. In such a situation, a person outfits himself against the constant and perfidious danger from individuals, from curses. A person speaks certain words, performs certain gestures, and bears an amulet.

It would be inaccurate to say that the Romans were obsessed with sex because of the frequent finds of phallic pendants and grotesque figures in excavations, and the frequently cited proverb bonus penis pax in domo. Let us leave aside Tiberius and Nero, who are perhaps better known for their debauchery than their political roles. Many have remembered Messalina, the wife of the emperor Claudius, who gave herself to passing strangers in the quarter of ill-repute Suburbia. Leaving aside the sensual lasciviousness of the aesthete and skeptic whose main care was to lead an inimitable and easy life full of pleasure, we should instead remember the anxieties of a person faced with the unknowns of life and death, the unease induced by human destiny. This is when superstition appears, which exists from the baneful influence held by certain words or images, and particularly certain individuals in terms of parts of their attire, or a certain eye color, or merely their presence. In such a situation, a person outfits himself against the constant and perfidious danger from individuals, from curses. A person speaks certain words, performs certain gestures, and bears an amulet.

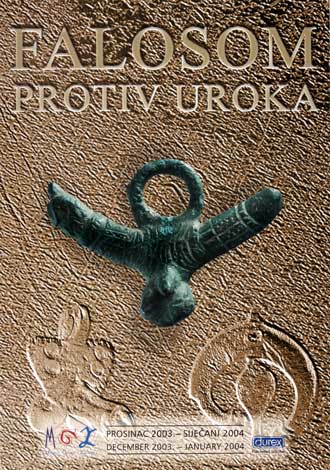

The phallus as an amulet was depicted in bone, ivory, stone, or metal in numerous pendants that were worn around the neck or on the belt, for the same reasons as the figures of deities, images of animals, colored beads, which represented a specific cure against illness and curses. Phalluses were worn by Roman women around their necks while their husbands were at war. Phalluses were depicted on Roman houses, on the vehicles of military commanders, and their size, form, and interpretation gave them meaning to the individual, and also protected them from evil wishes. The privileged wore phalluses of silver, and also of gold. It was expected that the phallus would not merely protect an individual, but also watch over acquired worldly goods, whether mobile or immobile. Roman tables in the form of hermaphroditic columns that depict naked sexual organs prevented bleeding and harm from the food placed on them. Lamps of phallic form with chiming pendants on them drove away evil spirits that circulated in the dark of the night. Phalluses with wings and paws seem to be ready to chase away anyone who would attempt to approach with evil intentions.

The phallus is often artistically transformed into a fish, with the glans representing the head. Two decorated or opposed phalluses joined at the scrotum may at first glance resemble a simple geometric game, but seen up close there is no doubt what they represent. Sometimes an inscription is found on them of an order to drive away an evil spirit (EPPE), or a greeting to visitors or friends, who will also be protected by the symbol (KAI, COI, KAICY, TIBI). Naturally, the question arises as to why the phallus was chosen as the protector against curses.

According to folk understanding, the integrity of a human being, which can be harmed by the evil eye, consists above all in the integrity of sexual function. Through the phallus the genetic map of a human being is transmitted, as creation forms a new life, new strength in the battle against evil. According to the opinion of Galen, which was to dominate throughout the entire Middle Ages, sperm were derived from the brain, and made their way through the spinal cord. Thus the phallus symbolized the east, the site and source of life, warmth, and light. It is also called the seventh human limb; it is the center around which seed circulate and the head from which seed issues. The eighth limb (female) faces it. The phallus delivers its seed into it, like a channel flowing to the sea.

According to folk understanding, the integrity of a human being, which can be harmed by the evil eye, consists above all in the integrity of sexual function. Through the phallus the genetic map of a human being is transmitted, as creation forms a new life, new strength in the battle against evil. According to the opinion of Galen, which was to dominate throughout the entire Middle Ages, sperm were derived from the brain, and made their way through the spinal cord. Thus the phallus symbolized the east, the site and source of life, warmth, and light. It is also called the seventh human limb; it is the center around which seed circulate and the head from which seed issues. The eighth limb (female) faces it. The phallus delivers its seed into it, like a channel flowing to the sea.

According to Sefer Yerira, the phallus does not have merely a procreative function, but also creates a balance on the level of the human structure and order of the world. Thus this seventh limb – the factor of balance in the structure and dynamism of man – is connected to the seventh day of Creation, the day of rest, and with the righteous who has the role of supporting and balancing the world. The phallus in various forms exhibits creative powers and is respected as the source of life.

In my own medical practice, I have heard several times from older patients when they had to strip naked that they were uncomfortable with someone seeing their “life” – while covering their sexual organs.

Making a fig or cocking a snoot, and specifically squeezing the thumb between the index and middle fingers, is in fact a depiction of the phallus in an opening between lips. This gesture, popular from the times of ancient Rome, has been retained on early amulets, and today is spread throughout the entire world in the form of “good-luck charms”. Perhaps it seems strange that a gesture imitating copulation should become a symbol that brings good fortune? It seems that the answer lies in the fact that this is a “gesture to avert”.

Making a fig or cocking a snoot, and specifically squeezing the thumb between the index and middle fingers, is in fact a depiction of the phallus in an opening between lips. This gesture, popular from the times of ancient Rome, has been retained on early amulets, and today is spread throughout the entire world in the form of “good-luck charms”. Perhaps it seems strange that a gesture imitating copulation should become a symbol that brings good fortune? It seems that the answer lies in the fact that this is a “gesture to avert”.

Many Mediterranean natives deeply believe in the power of the “evil eye”, which can bring bad fortune. One is never certain who does or doesn't have the evil eye, and thus it is wise to bear some protection. A gesture so shocking as making a fig (or cocking a snoot) will certainly draw the attention of a person with an evil eye, and thus someone who bears such an amulet will be spared from direct staring.

Naturally, the frequent finds of phalluses or erotic figures were not exclusively connected to defense from curses. The Roman writer Ovid in his poem Tristia described what was usual for the decoration of a wealthy Roman house: not merely was it painted with famous scenes from mythology but also with erotic images. Archaeological finds indicate that these erotic scenes were very common in all strata of Roman society. These paintings or figurines had various meanings. Some ensured fertility or induced good fortune, while some scenes were simply titillating or witty.

Objects with explicit sexual scenes were certainly common in the ancient world, but thanks to Victorian backwardness and prejudices that the material was vulgar, such objects were hidden for many years in inaccessible rooms of international museums, such as the erotic collection of the Museum of Naples (which has only recently been presented to the public), and the collection of the British Museum in London. The well-known collection of the Haddad family was recently presented, which abounds in examples of erotic sculpture and numerous amulets from the Egyptian and Roman periods.

Objects with explicit sexual scenes were certainly common in the ancient world, but thanks to Victorian backwardness and prejudices that the material was vulgar, such objects were hidden for many years in inaccessible rooms of international museums, such as the erotic collection of the Museum of Naples (which has only recently been presented to the public), and the collection of the British Museum in London. The well-known collection of the Haddad family was recently presented, which abounds in examples of erotic sculpture and numerous amulets from the Egyptian and Roman periods.

Numerous depictions of the god Priapus exist that are exhibited daily in many museums in bronze, silver, and terracotta. He is shown with an enormous phallus. The Romans never considered this image erotic, rather they displayed it publicly, keeping it in their domestic shrines so that it would ensure the fertility, better crops, and an increase in their domestic animals. For the Romans the display of a creature of humorous appearance with emphasized sexual attributes was always tied to the symbolism of good fortune.

In the Roman period, the phallus appeared on many objects of everyday use, such as lamps, vessels, gems, decorative disks, knife handles, and military equipment. Vessels in the form of a phallus exist that were used to store food for children. Female amulets appear more rarely, and amulets with a combined depiction of phallus and vulva are not that rare.

It is interesting to note the appearance of phallus amulets later in other parts of the world. The Thai term for a phallus amulet is palad khik, which means “venerated phallus surrogate”. These small charms, less than two centimeters in average size, were worn by boys and men on a ribbon around their waist below their clothing, above the real penis, in a belief that this would drive off any possible magical damage to the genital organs. It was not unusual for men to wear several amulets at the same time – the increase luck in games of chance, to attract women, to protect against knives.

It is interesting to note the appearance of phallus amulets later in other parts of the world. The Thai term for a phallus amulet is palad khik, which means “venerated phallus surrogate”. These small charms, less than two centimeters in average size, were worn by boys and men on a ribbon around their waist below their clothing, above the real penis, in a belief that this would drive off any possible magical damage to the genital organs. It was not unusual for men to wear several amulets at the same time – the increase luck in games of chance, to attract women, to protect against knives.

The term palad khik comes from the Shiva language and was probably introduced into Thailand from India via Cambodian monks in the eighth century. Vows and prayers directed to Shiva were engraved on the early amulets, and on later amulets these requests were combined with those to Buddha. Modern amulets have prayers and vows addressed exclusively to Buddha, sometimes written in an ancient style which modern Thai people can no longer read.

Dr Damir Kovač

(from the exhibition catalogue)

Pictures from the exhibition

.jpg)

photo Miljenko Gregl, ZCM

Exhibition catalogue

Exhibition catalogue

Kovač, Damir; Remza Koščević. Phallus Against Spells - The Archaeological Collection of Dr Damir Kovač.

Zagreb : Zagreb City Museum, 2003