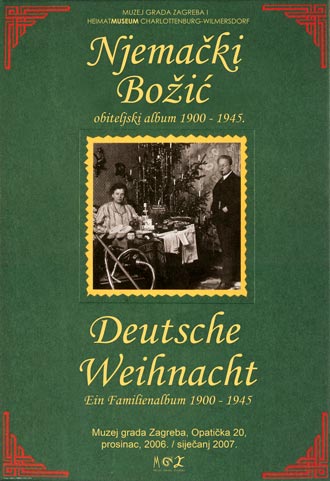

German Christmas - a family album, 1900-1945

Heimatsmuseum Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf - Berlin, guest appearance in Zagreb City Museum

Exhibition concept: Birgit Jochens

Curator: Nada Premerl

Exhibition design: Željko Kovačić

Poster design: Miljenko Gregl

They could almost have been forgotten, yet, nearly 50 years after their death, Anna and Richard Wagner, a hitherto totally unknown Berlin couple became known to the public. The reason was one of the most wonderful chronicles of life somebody can leave behind: a series of photographs, showing both of them over a period of four decades, year after year at a particularly tender moment, standing in front of their Christmas tree and their table of presents.

They could almost have been forgotten, yet, nearly 50 years after their death, Anna and Richard Wagner, a hitherto totally unknown Berlin couple became known to the public. The reason was one of the most wonderful chronicles of life somebody can leave behind: a series of photographs, showing both of them over a period of four decades, year after year at a particularly tender moment, standing in front of their Christmas tree and their table of presents.

It is purely by a quirk of fate, that we make the Wagners' acquaintance. An East Berlin family, mistaking the photographs as records of their own relatives, kept them for posterity. They were amongst the items left to them by their grandmother, who had lived in the other half of the city. During the last years of her life, the Wall had separated her from her grandchildren, who lived in Marzahn (East Berlin), and therefore she could tell them only a little about herself. Thus the knowledge about the grandmother's unusual friends who had taken these interesting photographs, had vanished for the time being. Things changed when, some years ago, the local museum of Berlin-Charlottenburg asked in press items for private Christmas photographs for an exhibition and received the packet of photographs from Marzahn.

After a first glance at the pictures, the museum staff became excited about them and decided to follow them up. This special kind of historical documentation of culture and civilization seemed unique, especially as these postcards threw glimpses on the remarkable era between 1900 and 1945. In the photographs one can see how the Christmas tree was decorated, what presents were exchanged, what the gifts tell about the daily life of those times, what clothes people wore on festive days... Besides, the photographs were dated carefully and were annotated as well.

As nobody really knew anything about Anna and Richard Wagner, old address lists and parish registers had to be examined in order to obtain initial information about the Wagners' life.

Richard Wagner, the man who so carefully completed his Christmas photograph series, year after year, was – one can almost guess – a civil servant, an assistant manager with the German Railways. Born in Berlin, he began his career in Essen and, with his young wife who came from Erfurt, he returned to live in Berlin in 1909. Here he later became a railway inspector.

During the longest period of their marriage they lived in the well-to-do middle-class area of the Bavarian Quarter m Schöneberg. The house in 5, Salzburger Straße belonged to the 'Civil Servants Dwelling Association' and had been built according to the plans of the architect, Paul Mebes, in 1907. Richard and Anna Wagner moved there in 1911, into a small flat.

They were amongst the influx of people who had rushed to the capital at the beginning of the century. At those times Berlin was the heart of Prussia and of the German Empire; the centre of administration, banks, trade and traffic. All these newcomers had caused a population explosion in Berlin. For such people the 'Dwelling Association' had built the "sound, low-cost, long-lease rental properties" close to Schöneberg town hall. These were equipped with electric light and bathrooms which, in those days, could not be taken for granted.

Apparently the Wagners remained childless. Their cat, Mietz, appears to have played an important role, as substitute, for several years. During the first years of the marriage the cat is always in the photos and always in quite an interesting pose. Though the Wagners could not be described as wealthy, they did not appear to lack anything either.

In their leisure time they preferred to go on bike rides, a very modern pastime, and to travel. Especially before the First World War, they benefited from the free travel tickets which were available to Richard Wagner, as they were to all employees of the German Railway Association. The Wagners travelled regularly by train to Italy, Bulgaria, Spain, Austria, Russia, Denmark, and very often to the mountains.

They seem to have had a sense of humour as we see from their photographs. Little sketches, for example, captured on New Year's Eve photographs, or comments on other photographs, indicate a preference for ironical distance, maintained to the end of their lives.

Above all, however, Richard Wagner was obsessed with photography. In this hobby he was ahead of his time. Whilst "amateur photography" first became popular at the beginning of the 1930's he had taken it up long before the turn of the century. He mainly produced 'stereoscopic photographs' as they had come into fashion in Europe and America in the early sixties of the last century. They consisted of a pair of photographs which, looked at through a special optical apparatus, a 'stereoscope', fused to an almost three-dimensional picture. Most of his Christmas photographs were taken by this technique.

Richard Wagner had spared no expense for his photographic equipment. In 1903 his 'Liliput', in reality a particularly flat and small 'Krügeners Flachdelta Kamera', made by the Company Wachtl from Vienna, cost 240 Marks, about a month's wages. Richard liked to experiment with his folding camera, or he made photographic layouts and photomontages.

Even when the persuit of his hobbby became risky, he did not give it up. In 1943 he even took photos of "bomb sites", such as the ruined town hall of Schöneberg – but, with a regard for his own safety, only from his balcony. In those times, reports of "attentive fellow-citizens" denunciating such prohibited activities piled up at local police stations.

The Wagners' Christmas photographs were taken for a special reason. They sent them to their friends as Christmas cards.

Richard Wagner went to great lengths in their production. Every year he changed the scenery a little, found out new ways of hiding the automatic release which on some occasions was apparently activated by Anna.

Although they may have been unconventional in some aspects of their lives, in these photographs the Wagners appear to be typical members of German middle-class society. During almost five decades of their marriage they hardly changed their living-room furniture. Articles which people bought for setting up home, had to last a lifetime. These were solid pieces of a stylistic mixture of 'Victorian', in Berlin a time of wild speculation called "Gründerzeit", and 'Art Nouveau' such as a plush sofa decorated with lace coverlets, a dresser, shelves with pewter tankards, jugs and nick-nacks, or the bureau with many drawers, which introduced an element of male severity. They did not forego the obligatory mountainscape in memory of their own journeys, and the "elevating" art of "the great masters" such as Böcklin's 'Toteninsel' (Isle of the Dead).

The Wagners followed the changes of fashion slowly. In the twenties, when Berlin gradually blossomed into the metropolis of "modern chic", this was largely owing to the ladies and gentlemen of the upper classes, to the "parvenus", or to the crowds of young loiterers and "artificial-silk girls" who in realitly had no money to spend. When "Belle Epoque" fashion with its figure-conscious, lace trimmed long dresses and suits abruptly finished, making way for the "Girl- and Garçonne-" style, Anna Wagner was already a mature woman. In her new sack dress she began tentatively to show a little more leg. Her husband was probably more concerned with the correct fitting of his suit. We seldom see him without a waistcoat, stand-up collar and tie, or later cravat. Only once – maybe in the exuberance of youth – he succumbed to a long-handled pipe.

The presents displayed for their friends show an upright middle-class attitude. There were mainly "utility items" on their gift table: fabrics, food, household utensils, money, shirts, stockings and, again and again, gloves; seldom Eau de Cologne, a watch or even jewellery. The search for eccentric surprises, so common nowadays, began for the middle-class only about four decades ago.

In spite of the limited selection, the Wagners' gift table shows a lot about the time and the changing situation of Germany.

On two occasions we see the couple in front of the Christmas tree dressed in winter coats due to wartime coal shortages. During two world wars and the crises of the Weimar Republic, they only enjoyed a few happy and financially stable years. Their membership in the 'Civil Servants' Dwelling Association probably became unexpectedly important for them since it provided its tenants with additional rations of coal and potatoes during those years of shortages. Nevertheless, the Wagners must have regarded their situation as so difficult, that they felt obliged to mark their expenses for birthday and Christmas gifts carefully on the back of their Christmas cards.

At the same time we learn something about their particular principle behind giving presents. They were concerned that they should spend the same amount on one another. Where gifts exceeded a certain amount, they wrote down explanations. These Christmas photographs even give us an impression of their political leanings. Like many employees of the German Railways, Richard Wagner seemed to have inclined towards conservatism. At any rate, the Emperor's portrait still hung on the wall above the sofa when William II had been in exile in Doom for many years.

On the other hand the photographs do not tell anything about the Wagners' attitude towards National Socialism. They can hardly have been spared from insights into the horrors of their time since they lived in a district of Berlin which had (7,1% opposed to the usual 1,0%) an extremely high rate of Jewish inhabitants. The Bavarian Quarter was therefore ironically called "Jüdische Schweiz"(Jewish Switzerland). "Schweiz" (Switzerland) is in German a sort of official nick-name especially for hilly and rich regions. At any rate, in this district in every third or fourth house there were Jewish flats, having been "opened or closed" by the authorities.

It was only thanks to the fact that the Wagners had been born "at the right moment" that this extremely voluminous and regular sequence of photographs could exist. At the beginning of the First World War, Richard Wagner had reached an age which exempted him from conscription, so he could continue spending his Christmas Days with his wife. However, it was the Second World War which saw an end to their partnership. Having suffered deprivations for years, which robbed Anna Wagner of her strength, she died in August 1945, at 71 years of age. Richard Wagner died shortly before Christmas 1950, at the age of 77.

They left records of four decades of German Christmasses representing a section of German everyday life. This chronicle was intended for the long term and bears witness to a persevering confidence unblemished by temporary adversities. Probably unconsciously the Wagners clung imperturbably to their habits and it is for this reason that for us they endure. Their photographs provide for posterity information which, in its unaffected private way, forms an important complement to cultural historical documentation or literary depictions of the Christmas festival. These mostly emphasize important events, forgetting the typical, mundane experiences which are part of everyday life.

Because so much which is contained in the photographs seems familiar, we can blend the pictures – those in our own imagination and those in the photographs – creating an endless Christmas story. Not everyone may love Christmas, but it keeps us all spellbound year after year.

Birgit Jochens